It is a paradox that, with the advent of biometric passports (ePassports), everything has changed and nothing has changed. ePassports certainly offer new levels of security. But, at the same time, they present us with new challenges of complexity. More work, not less. This article considers a range of approaches to secure personalization of ePassports.

By Duncan Stradling

PERSONALIZATION BASICS

To start from first principles, an ePassport is fundamentally a secure book with personal data which has to be protected. The first question is: what and how much data to include? The answer depends on the objectives which a government has for its ePassport program. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) document 9303 simply requires the contactless chip to store the same personal data that appears on the data page. That means all the data on the machine readable zone (name, date of birth, gender, passport number) as well as the facial image. But these elements together take up only 2 of the 19 data groups in the Logical Data Structure (LDS) of an ePassport, and something like 25 KB of the 72 KB currently used in most chips (even if the ICAO minimum is 32 KB). So there is clearly spare capacity which can be used if required.

There are several candidates to fill this spare capacity. For example, the European Union (EU) has decided to add fingerprints from 2009. Others may also do so. Even then, the fingerprints and the encryption to protect them will add something like a further 18 KB of data, still leaving more space. Governments or regional groups may want to add other data in due course. This might include other biometrics, e.g., the iris, which is already being used in a number of ID schemes in, for example, the U.S.A. and the Middle East. They may want to add other data for national use, for example, a national identity number which may be different from the passport number. This ¡®national¡¯ data could be security protected so that it can only be read by readers authorized by the country concerned. Of course, if there is a wish to take up all these options, care will be needed to avoid the risk of exceeding the available 72 KB.

This reinforces the need to establish clearly in advance all the functions which a government requires its ePassport to perform. Obviously, it must be ICAO-compliant. But will it also have to meet any regional, e.g., EU, standards? Or would it be helpful to include other registration details, e.g., the national ID number? A country which is introducing eGovernment systems at home may want to make its ePassport a full part of the system. New elements can always be added later, but it is always best to look at the whole picture at the beginning and futureproof as much as possible.

CENTRALIZED OR DECENTRALIZED ISSUANCE?

In most cases, governments will conclude that including biometrics will mean that citizens will need -- at least once -- to register at an office, rather than just sending an application form. At this stage governments may decide to go further, as in the United Kingdom, and interview all new applicants to check that they really are who they say they are before biometrics are used to fix their identity for life. Whatever approach is taken, biometrics add extra complexity and cost to the passport enrollment and issuing process. Security of course remains paramount. But governments are increasingly regarding the processing of applications and issuing passports not just as a legal duty but also as a consumer transaction -- and they are setting ever higher customer service standards for it.

In principle, it should be easier to maintain security at a single issuing site. The more complex the technology, the greater the economic arguments will also be for a single issuing site. But in a large country, there may still be advantages in distributed issue. For example, in Mexico, there are some 45 or so issuing sites, in Chile, many application sites but a single issuing site. Different circumstances will require different solutions.

Governments may wish to allow for online application, as is now becoming the case for some visas. But full online application will not be possible, except where the applicant¡¯s up-to-date biometrics are already stored on the central database. Even so, the latest version of ICAO Document 9303 makes clear that the facial image should be no older than six months when the application is made. Clearly this has implications on the long-term validity of stored images.

Countries will still wish to provide the facility for expatriates to apply for passports at a number of embassies overseas. The biometric element will call for new electronic, perhaps Web-based, data transfer systems, which will need appropriate security. It is certainly possible to equip overseas embassies to issue biometric passports under these conditions. However, some countries are seriously considering repatriating these processes as a result of the prohibitive cost of installing secure ePassport personalization operations in all or even some overseas embassies.

There will be constraints on how far customer service can be improved. As citizens, we would all like the process to be as quick and smooth as possible. However, some of the new, more secure, processes will take longer: live capture of facial images will require attendance in person at designated centers and, depending on the technology, may take some time. However, it is likely that the technology will develop relatively quickly and eventually become commonplace both in the public and private sectors.

TYPES OF PRINT PERSONALIZATION

Print personalization will still be as vital as ever to document security. No chip is infallible. There will be times when it will fail. Or it will break. And it is certain that criminals will take advantage of this vulnerability. Imagine a traveller arriving at the airport from the other side of the world and the chip in their ePassport cannot be read. What are the authorities to do? If there is nothing other than the chip to rely on, they could end up either sending home an innocent person, letting in a serious criminal or, even worse, a terrorist. In such circumstances, the border guards will need to be able to rely on the traditional security features, including a securely-protected data page.

There is an increasing range of options for secure print personalization, from paper with various kinds of laminate (thicker or thinner, with or without holographic features) to different kinds of plastic card pages, most obviously polycarbonate. There are differences in cost and complexity. De La Rue has looked extensively at all the current technologies and in our view each has its strengths and weaknesses -- none is uniquely preferable.

There is much to be said for a paper data page, with laser printing or now more commonly inkjet -- because of cost and the variety of types of ink which can be used. Now that the ICAO standard is to locate the data page inside rather than on the cover, a paper data page can take advantage of all the security features developed for banknotes, including most obviously a cylinder mold watermark. Laminates still vary considerably. There¡¯s a strong movement away from the old, very thick sheets which used to cover stuck-in photographs. In order to compare modern laminates, the most important point to consider is the difficulty of removing the laminate and how obvious any tampering will be.

Key features are the thickness of the laminate and the means of affixing it to the page, with or without a margin around the edge of the paper. We believe having a margin makes it even harder to remove the laminate undetected. To add extra security, it is possible to add an Optically Variable Device (OVD) such as a hologram; this is, of course, part of the EU standard.

There is also increased interest in polycarbonate data pages, personalized with laser engraving. These can look very attractive, with a similar appearance to a chipped ID card. Again, at the practical level, there are advantages and disadvantages. Cost is certainly a factor, but it can play both ways. A polycarbonate-based project can be considerably more expensive to execute, especially if it involves distributed issuance. On the other hand, laser engraving technology is less widely available, so more exclusive to governments. In principle, that should make it harder to counterfeit, though its exclusivity is undoubtedly diminishing. Indeed, some of the major national fraud detection agencies are identifying large numbers of counterfeit polycarbonate documents -- perhaps the technology is not exactly the same as the original, but the effect can be quite convincing. Another feature of laser engraving is that the whole document can only be in greyscale. Some people prefer an all color facial image; others claim that greyscale allows for greater precision.

There is no consensus on the way ahead for personalization techniques. For the government which is considering what to do next, there is little to be gained by specifying a particular system at an early stage in the project planning and tendering process. It is imperative that governments decide on the key elements of the system they want to introduce -- centralized or distributed etc. -- along with their security preferences, of course not forgetting the budget, solicit offers, and then review the range of options which the market can provide.

E-PERSONALIZATION

The new element in biometric passports is that it is now necessary to consider both electronic and physical elements: storing the data securely on both the document and, critically, the chip. This is where the Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) comes in.

Although in detail this is a complex science, the principle is simple enough. A digital signature has the same purpose as a human signature on a contract: to certify that the person signing is who he says he is and that he has the authority to sign. For a digital signature, you take a chunk of data (defined as the Logical Data Structure) and encrypt it using your private key (which only you have). Someone else can decrypt it, not using the same key, but using a public key which you distribute to them. And to prove that all this is really yours, you distribute your Digital Certificate which contains a copy of the public key and, at the next level up, a digital signature of a known Certificate Authority.

Now so far, we only have a way to prove that the data is genuine. We have not yet protected it. This is where access control technology comes in both Basic and Extended, with the former most prevalent at present but with many organizations (and suppliers) wanting to move towards the latter.

Basic Access Control (BAC) simply uses the data from the Machine Readable Zone (MRZ) as an algorithm to lock the data on the chip. This means that, to read the data, you have first to read the MRZ. That prevents skimming -- using a contactless reader in a clandestine fashion, for example, to read a passport in an envelope in the post, or in someone¡¯s back pocket or bag. It also prevents eavesdropping -- intercepting the transaction between an ePassport and a legitimate reader. (Figure 1)

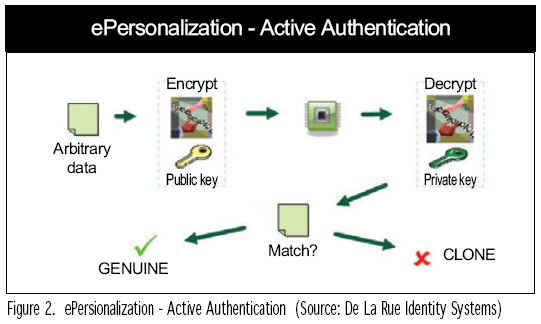

But this kind of authentication process is essentially passive. It does not prevent cloning the chip. For that, we need active authentication, which ties the data to a particular chip. This time it¡¯s the chip itself that generates a key pair -- the private key is held securely within the chip and the public key is held openly in the Logical Data Structure at DG 15.

When the passport is read, some arbitrary data is encrypted by the reading device using the public key and then sent to the chip. The chip then decrypts the data using its secure private key -- only that specific chip can do this. Then, if the decrypted data matches the original data, it proves that the chip is the genuine original because only that chip has the right private key, which is securely hidden and therefore couldn¡¯t have been copied or cloned. If it cannot decrypt the data, then it must be a clone (Figure 2).

Extended Access Control is required when sensitive data, which is not printed on the page, is to be included on the chip. So far, the most obvious example is fingerprint data. In short, it involves a two-way challenge process. Both sides must prove their identity. Not only does the chip use its digital signature to ¡®prove¡¯ that it is genuine, but the reader has to ¡®prove¡¯ that it belongs to a legitimate authority before the chip will allow its data to be decrypted. This is a much more complex process and will require all the participating authorities to exchange the certification information of both documents and readers. In practice its use is likely to be limited for the time being to individual countries or regional groups. For example, the EU will be operating such a system to allow for the secure reading of fingerprints on EU countries¡¯ passports from 2009.

So, while Extended Access Control will bring much greater security to both storage and reading, it is complex, requires active participation from all the concerned authorities and is also much more expensive to implement.

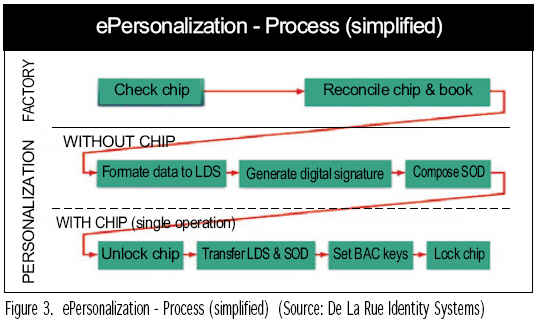

Putting all this together, a simplified version of the e-personalization process can be seen in Figure 3.

Of course, greater complexity would be required in order to incorporate the ePassport into a wider eGovernment system where other data will be used and integrated into a wider range of solutions.

ePassports have indeed changed everything and they¡¯re changed nothing. The main criteria: security, customer service, efficiency and cost-effectiveness remain the same. But the complexity, and potentially the cost, has increased and the options have multiplied.

Most important of all is to be clear at the start about requirements and priorities. And it is best to be open-minded about the possible solutions. And for governments and suppliers to work in partnership to determine what best fits the particular circumstances.

Duncan Stradling is Technical Director of De La Rue Identity Systems (www.delarue.com).

For more information, please send your e-mails to swm@infothe.com.

¨Ï2007 www.SecurityWorldMag.com. All rights reserved.

|